The Future Arrives in the Classroom

We are living in an age where education is transforming faster than at any point in history. The very definition of learning is changing. Classrooms are no longer confined by walls, knowledge now flows through digital platforms, online communities, and artificial intelligence.

Today, students across the globe are being trained not just in subjects, but in skills of the future. They are learning how to build apps using low-code platforms, experiment with artificial intelligence, and engage with large language models like ChatGPT to enhance their creativity and productivity.

The conversation about education is increasingly skill-based. Traditional rote learning is giving way to experiential, adaptive, and personalized systems powered by technology. Students in developed nations, and in emerging urban centers, can now access a world of opportunity through their screens. They are preparing for jobs that didn’t even exist a decade ago: data scientists, AI ethicists, machine learning engineers, prompt designers.

For many, this is an exhilarating moment. Education is being reimagined as a bridge to future opportunities, a tool not just to survive, but to thrive in a world that demands innovation.

But not everyone is on this bridge.

A Parallel World in the Tea Gardens

Travel east to the green tea gardens of Sylhet and Moulvibazar, and you enter a different world, one that seems frozen in time. Here, in the heart of Bangladesh’s tea estates, generations of workers have lived under systemic exploitation for 171 years.

The lush landscape hides a painful truth. Children born into these communities inherit not just poverty, but the weight of an oppressive system that has barely changed since colonial times. While the rest of the world debates the impact of AI in education, these children are denied even the bare minimum of learning.

Schools in tea estates are often little more than fragile structures. Many lack enough teachers; textbooks are outdated or missing altogether. Classrooms are overcrowded, and the quality of teaching suffers under chronic neglect. In some estates, children must walk miles just to reach a functioning school.

The result is devastating: literacy rates among tea worker communities remain significantly below the national average. According to multiple studies, many children drop out before completing primary school. Some are pushed into child labor, helping their parents in the tea gardens. Others, especially girls, are married off early, cutting short their right to education and future independence.

While the world prepares its children for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, these children are locked out of the first step of learning: basic literacy.

171 Years of Exploitation

To understand why this gap exists, we must look back.

The tea industry in Bangladesh traces its roots to 1854, when British colonial rulers brought indentured laborers from different parts of India to work in the Sylhet tea gardens. These workers were cut off from their homelands, trapped in debt bondage, and subjected to inhumane working conditions.

Generations later, the cycle continues. Tea workers in Bangladesh earn some of the lowest wages in the country. Even after decades of independence, their access to land, healthcare, and education remains severely restricted. The exploitation is not just economic but systemic, woven into the very structure of how the tea industry operates.

Education, the one pathway that could have broken this cycle, was intentionally neglected. Colonial masters feared that an educated workforce would resist exploitation. Post-independence, governments failed to meaningfully change this trajectory. The result: an inherited cycle of illiteracy and poverty spanning nearly two centuries.

The Present Reality

Statistics paint a bleak picture.

- Tea workers in Bangladesh earn an average daily wage that is barely enough to survive.

- Child labor is common, as families rely on every possible hand to make ends meet.

- The dropout rate in tea estate schools is disproportionately high compared to national averages.

- Access to secondary education is rare; higher education is nearly unattainable.

This means that the children of tea workers are trapped in the same conditions as their parents, unable to climb out of poverty, unable to access opportunities, unable to break free from 171 years of exploitation.

Meanwhile, outside this world, the global conversation is about preparing children for jobs of the future. The gap is not just economic, it is existential.

Why Education Matters

Education is not just about literacy. It is about dignity, freedom, and the ability to choose one’s path in life.

When a child in a tea estate learns to read, write, and think critically, they gain more than knowledge, they gain agency. Education empowers them to question exploitation, demand fair wages, and imagine a future beyond the tea gardens.

We have seen examples of this in Bangladesh. Where NGOs and community-led initiatives have introduced quality education, children from tea estates have gone on to pursue university degrees, find meaningful employment, and return to uplift their communities.

These stories prove one thing: the cycle of exploitation is not unbreakable. It can be dismantled with education.

The Cruel Discrepancy

The irony is hard to ignore.

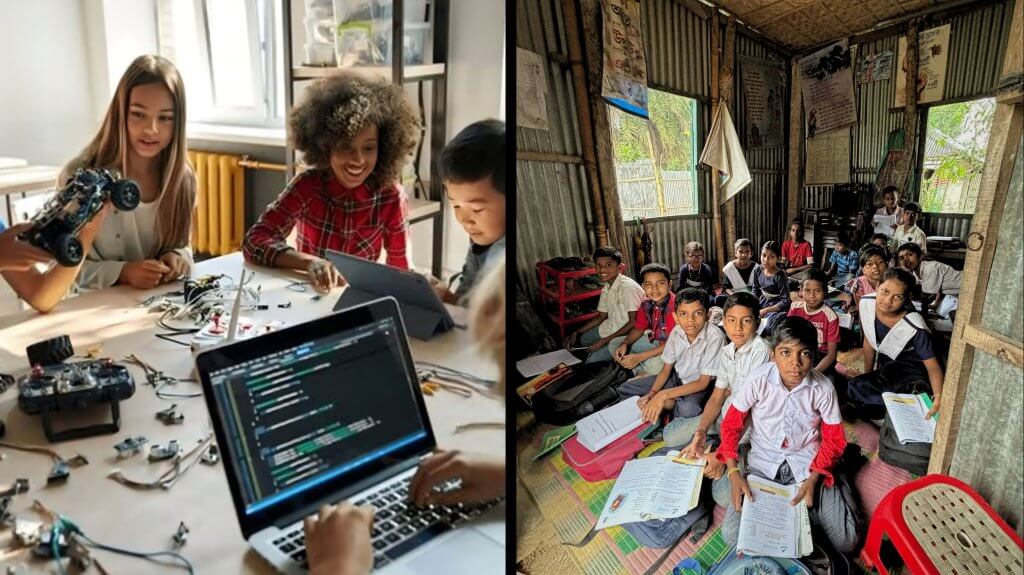

In one corner of the world, students are debating how AI might replace jobs. In another, children are denied the most basic skills needed to get any job beyond manual labor.

While the world talks about “digital natives,” tea estate children are not even given the chance to be literate natives. While global education systems experiment with robotics, coding, and the ethics of machine learning, these children remain trapped in chalkless classrooms, their futures written not in opportunities, but in centuries-old chains.

This is not just a gap; it is an injustice.

A Call for Change

The world cannot afford to have two parallel education system, one that propels children into the future, and another that keeps them shackled to the past.

We need urgent investment in education for marginalized communities like tea workers. This means building better schools, training teachers, ensuring access to resources, and creating pathways to higher education. But more than that, it means acknowledging education as a fundamental right, not a privilege for some, but a necessity for all.

If we can teach a child in the West how to build artificial intelligence, we can certainly ensure that a child in the tea estates learns to read and write.

The promise of education is not just individual, it is generational. One educated child can transform a family. One educated family can inspire a community. And one empowered community can break a cycle of 171 years.

Conclusion

As the world celebrates the transformation of education through AI, machine learning, and skill-based systems, let us not forget those still denied the simplest form of learning.

Education should not be about some children leaping into the future while others remain chained to the past. It should be about every child, whether in Silicon Valley or Sylhet, having the chance to dream, to learn, and to break free.

The question is not whether we can create this change. The question is whether we choose to.